Writing

Bridging Strategy & Delivery: Healing The Divide Between UX Design & Product Leadership

Everywhere you look, you see design leaders wrestling with big, existential questions. What happened to the promise of UX, what's up with product, and where do we go next?

I've spent the last 15 years building a career in UX Design. For most of that time, the path forward felt clear. Over the last few years, it's been harder to see.

I followed a fairly standard career progression. Starting as a young intern fresh out of school, I gained exposure to the field, and eventually progressed to a Senior UX Design role where I had plenty of opportunity to hone my craft. Eventually, I moved into a Director-level position leading teams and increasingly complex work.

There was no hopscotch across disciplines — just steady progression, new challenges, and growth within the field.

The Promise of UX

Coming up in design just after the iPhone, I was taught to believe in UX's role as a strategic function. That building the right thing was just as important (if not more important) than delivering the thing. Any practitioner knows that aesthetics are an important component of design, but success also requires deep understanding of the problem, users, and the business environment.

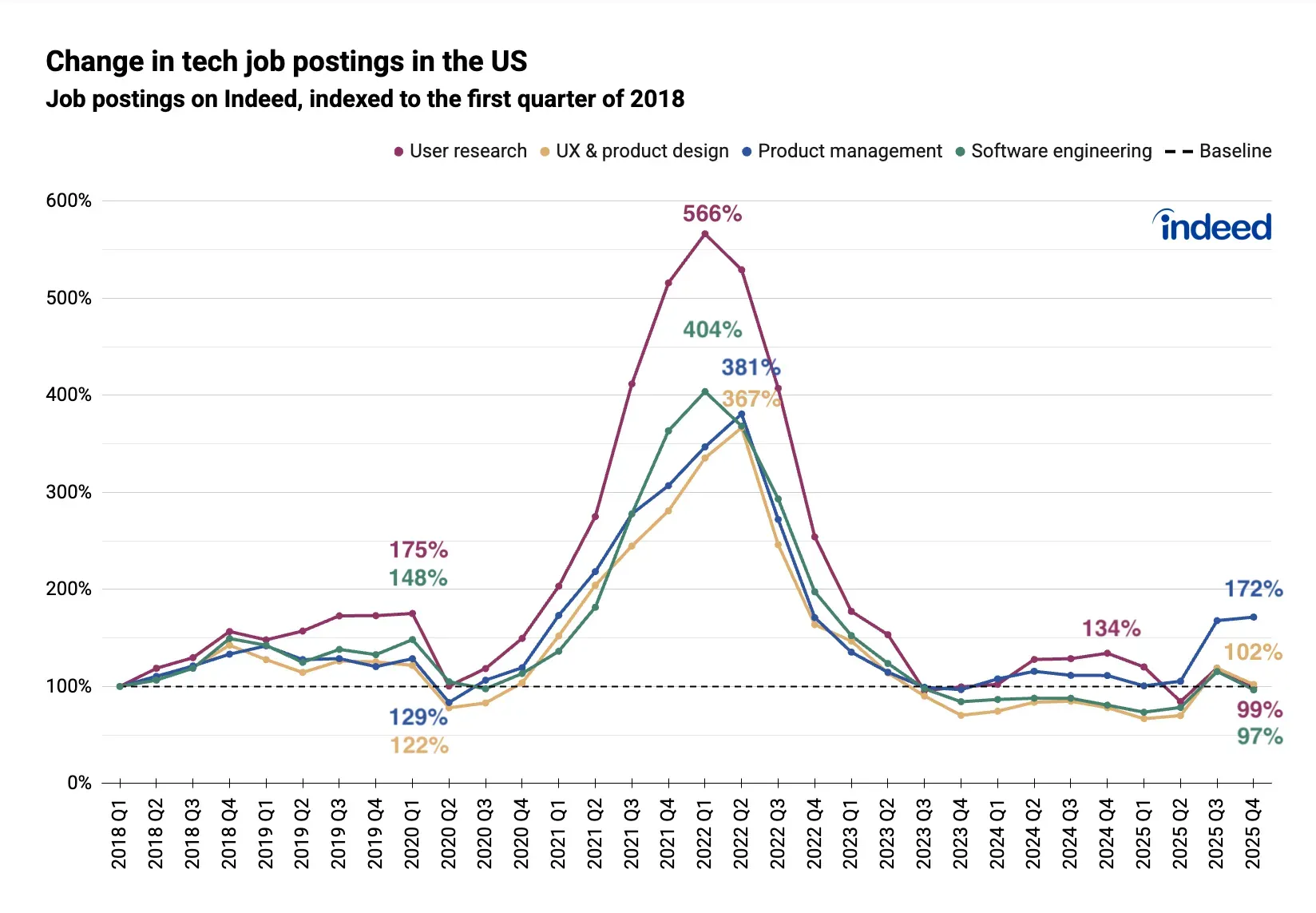

UX was in demand. Case study after case study proved the power of user-centred design, and businesses wanted more.

Designers talked about using the momentum to win a seat at the table, and some of the world’s largest companies created executive roles for design leadership. There was a sense that design had finally arrived — that user-centric thinking had proven its value and the real work could begin.

And yet, looking around these last few years, it's hard not to feel as though something went awry. Everywhere you look, design leaders are wrestling with big, existential questions, and user experience teams are either being retitled, or disappearing from org charts.

Looking across the industry, it can feel as though UX Design Directors have become an endangered species.

The Current State of UX

Unfortunately, the rising tide that once lifted the field has receded. What's left behind is an uncomfortable sense that the assumptions and bedrock principles we built our professional lives on simply aren't in demand anymore. Markets have shifted. There are newer, shinier toys competing to be the next big thing.

It's that stark realization that's led so many experienced designers, especially those in leadership positions, to question not just their role, but the system they're operating in. Looking back on the state of the field he helped to pioneer, Jesse James Garret observed the following:

“The more seasoned a UX person is, the more likely they are to be asking whether realizing user-centered values is even possible under capitalism.”

-Jesse James Garret

I've certainly felt that dissonance. In fact, I've even gone as far as sharing a conference talk on the technology industry's attempt to disrupt itself through enshittification.

And, while I don't think that it's all doom and gloom for UX, you can't deny that the ground has shifted.

How We Got Here: The Split Diamond

To understand how to move forward, we first need to understand the assumptions, shared beliefs, and systems that brought us to this moment.

Designer as Hero

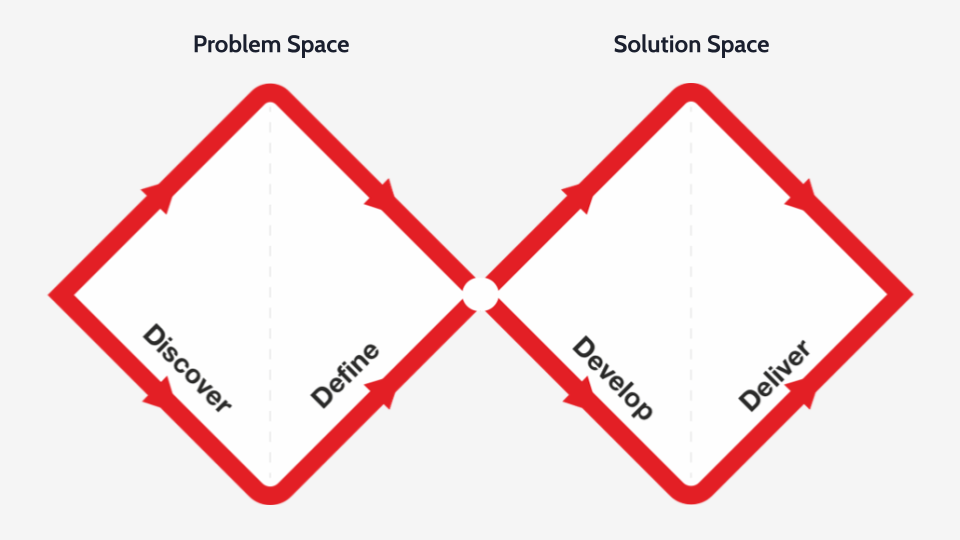

The classic double diamond model outlines a design process in which designers have ownership of both the problem space (discovery & definition) as well as the solution space (development and delivery). Note that "development" and "delivery" here are used in the context of design, not technical development.

It's an elegant visualization demonstrating a process where designers expand the possibility set before honing in on a direction. Working through solution delivery similarly involves exploring and developing multiple alternatives, before landing on the strongest solution with a full understanding of the tradeoffs and possibilities.

This process of diverging and converging is at the heart of design practices the world over. And the model works when design has wide-ranging ownership. When looked at through the lens of an individual designer, the diagram brings to mind heroes of design — people like Dieter Rams, Johnny Ive, Alan Cooper, or Susan Kare.

The theory isn't wrong.

But in modern product development, where problems are too complex for a single individual, design becomes a team sport. A design process that puts the designer at the centre of all things sets false expectations for how design works in modern product teams.

Design Got Put In The Delivery Corner

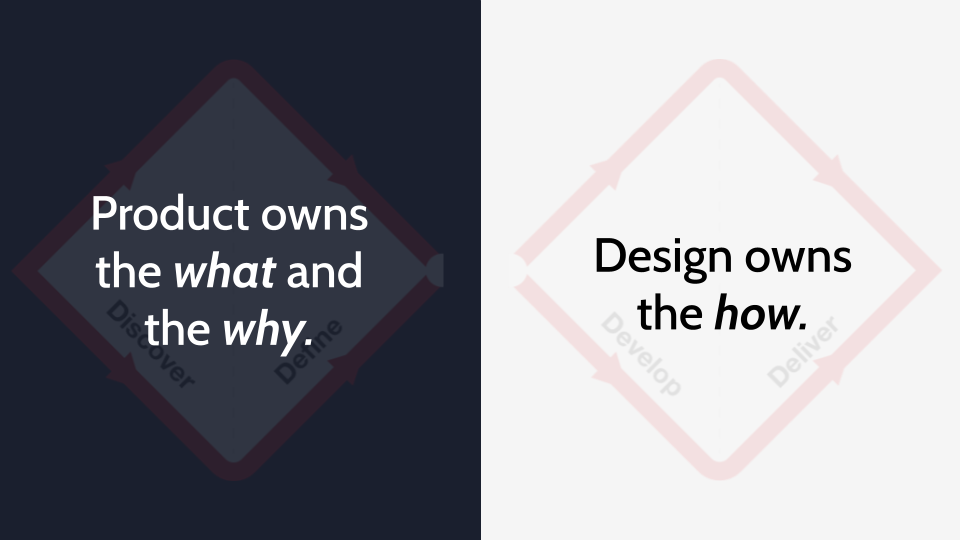

There's a good chance you've heard the expression "product owns the what and the why; design owns the how." This statement leaves no room for ambiguity, and it brings into focus an uncomfortable truth for designers — if product owns the problem space, then design's ownership over the double diamond is more aspirational than real.

By splitting the diamond, design's role is reduced to execution and delivery — polishing experiences where the decisions that matter are made by others. Some exceptional designers might influence these decisions, but it's still someone else's decision to make.

And this reality is true for designers in all types of organizations — even designers who work in organizations without well-developed product management practices tend to take their marching orders from somebody in a more business-centric role.

So how did this happen? There's no shortage of easy targets to pin the blame on.

For one, Design Thinking made it possible for organizations to separate the "thinking" and strategizing aspects of design from the "doing" (lack of actual results from design thinking processes notwithstanding). Similarly, the rise of agile and scrum workflows put pressure on strategic design deliverables that don't fit easily within the time constraints of a two week sprint.

Of course, many theorize that the rise of bootcamps played a role, flooding the market with UI designers who knew how to make screens look good, but without the depth of experience or training to navigate ambiguity in complex problem spaces.

But more than anything, I believe that the current state of design comes down to three simple truths:

- Design didn't want to be accountable for outcomes. Designers have traditionally worked towards definitions of quality and judgement, like surprise, delight, and intuitiveness. We tend to avoid taking accountability for business outcomes like revenue, sales, and efficiency — leaving a gap for others to fill.

- 'Good enough' got a lot easier. In recent years, the bar for 'good enough' design has dropped dramatically. Common use cases in digital product design can be solved with established best practices rather than reinventing the wheel, and design systems make it possible to ship acceptable experiences with limited involvement from the design team.

- Product spoke the language that business leaders understood. Finally, product management showed up speaking the language executives were comfortable with. While designers argued for principles and process, product spoke in the language of revenue, growth, and efficiency — with pragmatism for business realities like time-to-market and prioritization.

To be clear, none of these were intentional missteps by design leaders. You could make strong arguments for why each truth was logical when designers were in demand.

But markets shifts accelerated the divide, pushing design into the delivery corner, and expanding the chasm between strategy and delivery.

Tension, Frustration & Misunderstanding

For strategic designers who developed skills in problem discovery and definition, it can be deeply jarring to be told "that's not your job," especially when it's done without acknowledgement for past successes. And for younger designers taught an idealized version of the design process, the result is frequently disillusionment and feelings of resentment.

But tension exists on both sides of the divide.

For their part, product leaders find themselves under constant pressure to deliver and demonstrate momentum. They're expected to deliver results under uncertainty, but without the trusted process guardrails design teams use to navigate ambiguity.

Product leaders also feel the strain of aligning teams with different, often conflicting, incentive structures and agendas. Navigating this space requires a constant balancing act, a delicate dance that avoids burning trust or stepping on toes.

Left unchecked, it's human nature for tensions to devolve into an "us vs them" attitude where each side begins to resent the other.

Design and Product have different ways of thinking, with distinct values and principles that often lead to misunderstanding.

Craft Alone Is Not The Answer

When these tensions go unaddressed, design leaders have tended to fall back to more comfortable territory: craft and taste. As strategic influence erodes, they hold up delivery excellence as the path forward.

But this is retreat, clinging to delivery skills in order to maintain relevance. By staking design's value on an ever-rising bar of execution craft and subjective qualities like taste and judgement, we accept the premise of the split diamond — that design's most valuable contribution is decoration, not understanding.

It's likely that some designers would be content focusing purely on execution without the hassle of dealing with the business. But for those who developed strategic skills and sense-making abilities in order to shape direction, retreat means either abandoning capabilities they spent decades developing, or leaving the field entirely.

Thankfully, there's another option — one that leverages UX's traditional strengths in empathy and understanding. But it requires re-examining our assumptions about what winning looks like. In part two, we'll explore the role boundary spanners play in helping to bridge the divide, and discuss possible paths for designers at different stages of their career.

This article is part of a three-part exploration into the overlapping responsibilities of UX Design and Product leadership. Please consider signing up for email updates as the series continues.